The police and security forces beat up protesters. Hooligans attack candidates and destroy campaign ads. Anonymous groups spread threats and rumours online to discourage voting, running for office, or to sow mistrust.

This kind of election-related violence was widely covered by international news agencies in 2024, dubbed the “super year” for elections. The term “super year” might sound grandiose, but its use is justified. In 2024, nearly half of the world’s population – around 3.7 billion people – had the chance to vote, with elections held in over 60 countries. Many of the voters recently reached adulthood, and as a result, they were able to cast their votes for the very first time.

Research institutes are still collecting data and analysing the scope of election-related violence in 2024, but based on news reports, it is already evident that such violence has occurred across multiple continents in various forms.

Any form of election-related violence or interference is alarming as it threatens any country’s democratic progress.

Elections are one of the most significant ways for citizens to influence decision-making, both in liberal democracies and in hybrid regimes, where civil and political liberties tend to be more restricted. Therefore, any form of election-related violence or interference is alarming as it threatens any country’s democratic progress.

It has long been assumed that election-related violence reduces voter turnout and undermines trust in public institutions and electoral processes. However, more recent studies suggest that the reality could be more complex. For instance, some research indicates that in Africa, election-related violence can even increase political mobilisation, particularly in areas where support for the opposition is strong. This happens because election-related violence can motivate voters to stand firm against intimidation and actively defend their right to participate.

Different perpetrators

Election-related violence dates back to ancient Greece and still exists today in various forms. Perpetrators include states, armed groups, organisations, and groups linked to political parties, as well as religious and traditional leaders.

It can target voters, candidates, private property, and public infrastructure and occur at various stages of the electoral cycle, from candidate nominations to election day and its aftermath.

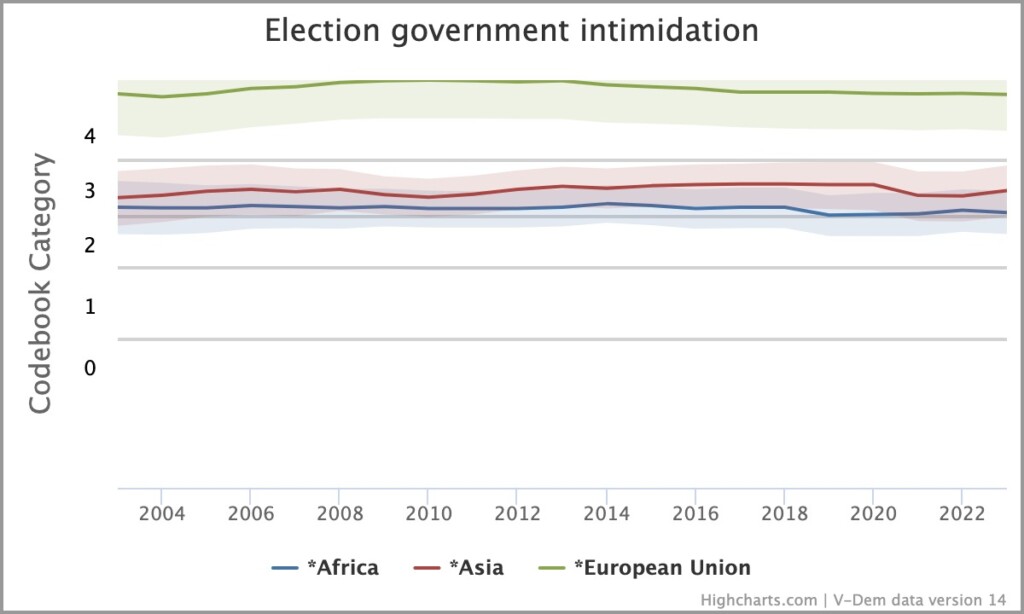

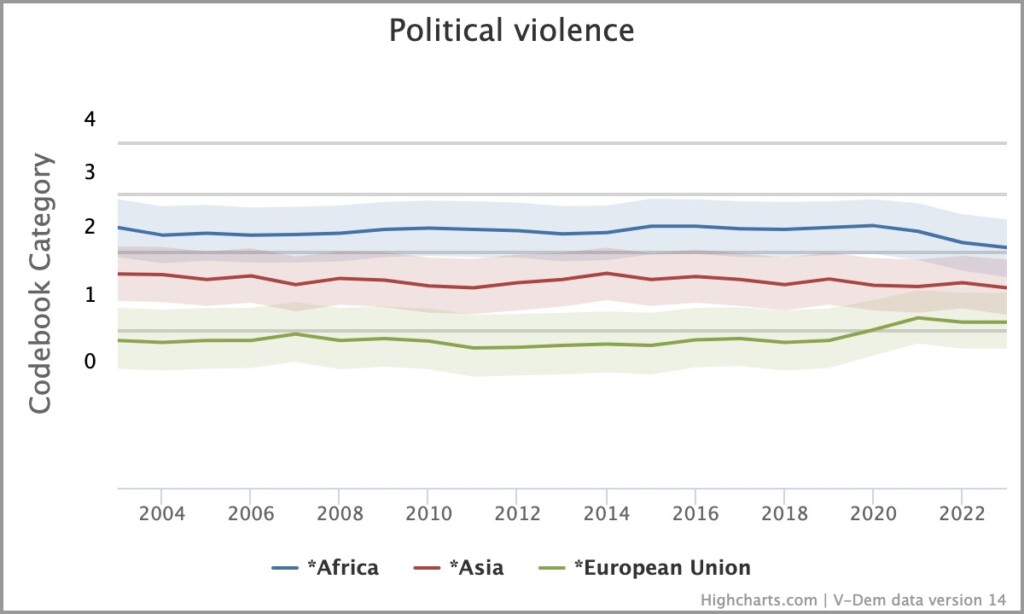

According to data compiled by the V-Dem Institute measuring democracy, election-related violence targeting voters has been minimal in the EU over the past twenty years. In Africa, such violence has not increased, though it still occurs sporadically.

Among the victims of such violence in 2024 were voters in Senegal, who faced violent crackdowns by security forces after the now-former president proposed postponing the elections.

When the elections in Senegal were eventually organised, electoral observation missions deployed by the European Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), considered them fair and well-organised.

In addition to voters in Senegal, voters have also been at risk in the Comoros and Mozambique, where violence erupted after the 2024 elections. In the Comoros, crackdowns by security forces resulted in one fatality and in Mozambique, post-election clashes have, according to Al Jazeera, led to the deaths of at least 30 people.

Violence by non-state actors targeting voters or the opposition has increased slightly in Europe. In Africa and Asia, such violence is more prevalent than in Europe, and decreased slightly in Africa. Nevertheless, the ‘super election year’ served as a stark reminder that election-related violence by ideological groups still occurs.

For example, in France, during the 2024 parliamentary elections, over 50 candidates and party activists reported being subjected to assaults. One of them was Prisca Thevenot, a candidate for the Renaissance Party, who, in an interview with the Associated Press (AP), reflected on the connection between verbal and physical violence following an attack.

“The symbolic violence of words was quickly replaced by physical violence. We are still a bit shocked … I remain mobilized”, said Thevenot in an interview with AP.

In the lead-up to the elections, candidates and parties from across the political spectrum condemned election-related violence in France.

In India, candidates from the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) fueled tensions by targeting Christians and Muslims during their campaigns, according to reports by Human Rights Watch (HRW). After the elections, Muslims were attacked or had their homes destroyed due to unsubstantiated allegations of cow slaughter. India’s Election Commission observed that such attacks were especially common in regions where BJP had lost support.

Election-related violence can occur out of sight and behind closed doors

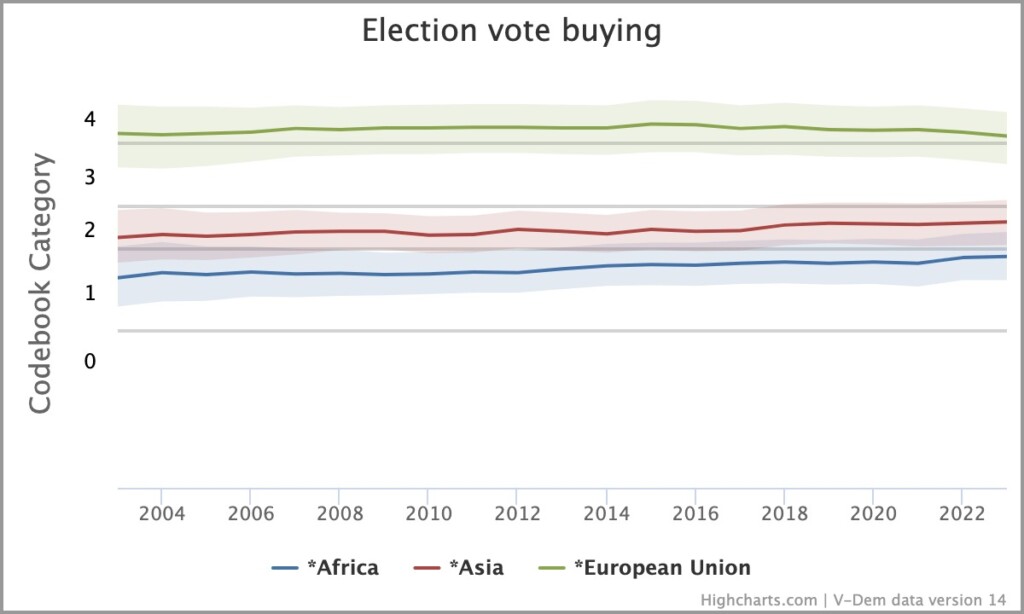

Election-related violence isn’t limited to physical acts of aggression. In many countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, researchers have extensively studied intimidation, vote-buying, and clientelism – in other words situations and relationships where a political party or actor offers benefits to their supporters in exchange for votes or services. In academia, these practices are commonly referred to as electoral manipulation.

According to some academics, electoral manipulation is a more common form of election-related violence in Africa than, for example, violent crackdowns on demonstrations.

Subtle forms of intimidation and vote-buying are also harder to capture in visually striking news images, which is one of the reasons they receive less coverage in the media and the public debate on election-related violence.

According to the V-Dem research institute, vote-buying still occurs in Africa, although it has decreased over the past twenty years. Nevertheless, during the “super year” of elections, reports emerged of vote-buying in Ghana ahead of the 2024 parliamentary elections. Additionally, the EU noted some isolated instances of vote-buying in at least one province in Senegal ahead of the country’s presidential elections.

In 2024 there were reports of vote-buying outside Africa, such as in Georgia and Moldova, where parliamentary and presidential elections were held in October and November. Additionally, lawyers have debated whether American billionaire Elon Musk’s million-dollar lottery in swing states ahead of the U.S. presidential election constitutes illegal electoral manipulation.

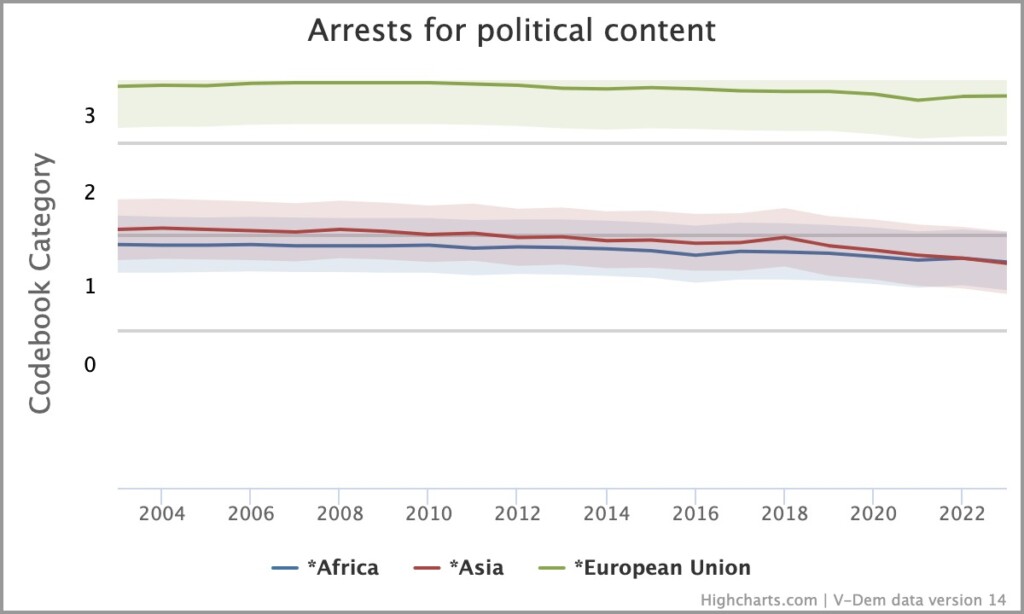

Electoral manipulation also includes the harassment and imprisonment of members of the opposition or individuals who criticise the government before the elections, often on fabricated or politically motivated charges. This occurred, for example, ahead of Tunisia’s 2024 presidential election, in which the incumbent president won with over 90 per cent of the vote. Voter turnout in Tunisia’s presidential election was around 29 per cent, the lowest figure for a presidential election in the country’s history since independence.

Elections are not isolated events

In countries struggling with civil war or its aftermath, elections can trigger or further escalate violence. In some cases, the turmoil and instability may prompt leaders to determine that holding elections is impossible.

This was the case in South Sudan in 2024, where the first elections since the country’s independence in 2011 were planned. However, it now seems like the elections will be delayed until 2026.

“This was inevitable but a regrettable development given the deep frustration and fatigue felt by the South Sudanese people at the apparent political paralysis and inaction of their leaders to implement the peace agreement and deliver the long-awaited democratic transition,” said Nicholas Haysom, Special Representative for South Sudan and Head of UNMISS.

Some research suggests that the risk of electoral violence increases during tense and polarising campaigns. Such violence tends to be slightly more common in areas with strong opposition support.

Some research suggests that the risk of electoral violence increases during tense and polarising campaigns.

For example, in Pakistan, the military and police have a record of carrying out violent crackdowns in areas where support for the opposition is strong. This continued during the 2024 elections, which were marked by several violent clashes between party activists and the military.

In Pakistan, the state was not the only actor engaging in violence. The terror group ISIS attacked party offices ahead of the elections. Additionally, the Balochistan separatist movement carried out multiple attacks on polling stations using hand grenades. These attacks carried out by various groups increased as election day approached.

Future challenges

The internet’s rapid expansion has opened up new avenues for political participation. In the early 2000s, there was widespread optimism about the internet revolutionising democracy and strengthening it significantly.

There’s still some truth to that idea. The internet has made information more accessible than at any other time in history. However, it has also become a powerful tool for governments and extremist groups to engage in harassment, intimidation, and surveillance.

In many countries across Africa and Asia, activists are arrested for posting political content on social media. For example, in Bangladesh, authorities detained citizens for criticising the government on social media ahead of the 2024 parliamentary elections, according to Human Rights Watch.

Election-related violence, like other forms of violence, often has a gendered aspect and can disproportionately target minorities. For example, in Ireland’s last local elections, 36 cases of harassment were reported. Thirteen of these incidents involved candidates from diverse backgrounds who experienced xenophobic harassment.

In Ireland, candidates were not the only ones facing harassment – instead, members of their teams were also targeted. For instance, volunteers campaigning for Suzzie O’Deniyi, a candidate of Nigerian descent running for Limerick City Council, faced racist abuse and threats during the campaign.

According to a 2016 study, women’s participation in politics in Europe, both during and outside the electoral cycle, is obstructed by sexually charged psychological harassment, much of which occurs on digital platforms.

While election-related violence has declined in recent years, its forms have shifted and, in some cases, intensified.

Ahead of the “super year” of elections, the Vice-Chair of the UK delegation to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) emphasised that the harassment and intimidation of women on digital platforms is one of the most significant challenges threatening the future of democracy. She also warned that advances in artificial intelligence could exacerbate these threats, particularly through deepfake videos.

Despite some setbacks, the year 2024 was, in many ways, a celebration of democracy, with a record number of people casting their votes. At the same time, it exposed the many faces of election-related violence. While such violence has declined in recent years, its forms have shifted and, in some cases, intensified.

Nevertheless, many of the challenges ahead can be tackled. Political parties, organisations, public institutions, and everyone participating in the public debate play a crucial role in condemning election-related violence and defending the civil and political rights of voters, candidates, and activists.

Perhaps most importantly, 2024 showed that, despite violence, people around the world remain determined to participate and make their voices heard – a powerful reminder that democracy still holds great hope for the future.